This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

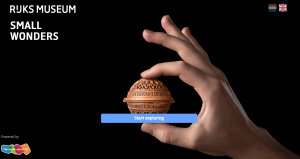

Exhibition Review of ‘Small Wonders’, June 17 – September 17 2017, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Although the glory of the Dutch Golden Age seems to garner the most attention (and museum-space) throughout the Netherlands, and particularly in Amsterdam, a new exhibition at the Rijksmuseum concentrates on painstakingly intricate carvings from the late Middle Ages. The exhibition includes inexplicably tiny figurines, prayer nuts, skulls, coffins, and altarpieces, all of which are masterfully carved.

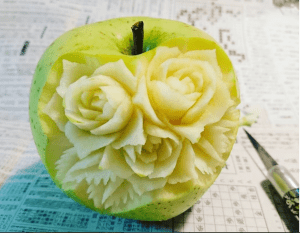

Even by today’s standards, the carvings go above and beyond the call of duty. I recently stumbled upon the intricate ‘Thai carvings’ of a Japanese artist named Gaku, who carves fruits and vegetables in an intense version of mukimono, the tradition of creating art with one’s food (and your mum always told you not to play with your food!).

Although Gaku’s carvings are quite impressive, the artists of the Middle Ages lacked X-Acto knives with which to create their impressive carvings as well as the Internet to spread their name and fame. After four years of collaborative research between the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, New York City’s Metropolitan Museum, and the Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam, this exhibition has been organised to reveal the cultural significance and production of these small wonders.

Although a smaller exhibition on these wood carvings was held at the Art Gallery of Ontario last year (November 2016-January 2017), the exhibition at the Rijksmuseum includes the largest collection of these micro-carvings ever collected into one place. Of the approximately 130 micro-carvings known to be in existence today, at least 60 will be on display in the Rijksmuseum’s Philips Wing.

Who made them?

One of the major discoveries throughout this research is the answer to the question of who actually made these minute carvings. Due to the relative consistency among the prayer nuts, the researchers at the Rijksmuseum have deduced that they were all produced in one workshop led by Adam Theodrici (‘Adam Dircksz.’). During this time, a master artist would often lead a workshop of apprentices who would learn to create in the style of the master; each of the apprentices would aim to create a ‘masterpiece’, meaning an art piece that has, almost literally, surpassed that of the master. With that in mind, it makes sense that so many of these prayer nuts would look so similar to one another.

Furthermore, Adam Dircksz.’ workshop was based in Delft, a surprising finding considering that art historians often presume that Flemish/Dutch art of the late Middle Ages mainly flourished in the southern provinces and modern-day Belgium. This northern workshop uncovers more of the art historical narrative at play in the late Middle Ages.

Purpose

Another important question regarding these boxwood miniatures is what purpose did they serve? Rijksmuseum researchers have concluded that the prayer nuts were mostly used for private, individual meditation, drawing viewers in with specific and unique details to meditate and be entertained for longer periods of time. This is particularly notable in the Metropolitan Museum’s micro-carving of the Crucifixion of Christ before Pilate: if you look closely, you’ll see a small figure on the front of the piece wearing glasses, almost as if to invite the viewer for closer, more intimate investigation.

Although you can get a good look at these pieces in the Rijksmuseum itself — the exhibition designer left plenty of room around each piece to invite closer inspection by visitors — you can also get a microscopic look at these pieces on the Rijksmuseum’s website dedicated specifically to this exhibition. Each of the eight pieces highlighted on this website provides several opportunity for a deep dive into the aesthetic qualities of the object, but the website also offers more insights and interpretations into specific pieces and features of each of the objects, which comes in handy if you are not particularly acquainted with all of the various ins and outs of late medieval Biblical stories and culture.

Overall, this exhibition is an enticing insight into a period that is often disregarded (at least in light of the Dutch Golden Ages and the Renaissance), but may also shed some light on the period preceding the Dutch Golden Age, for those of you who are interested in Dutch history, art history, and society.

The Rijksmuseum is open every day from 9.00AM to 5.00PM; the exhibition Small Wonders is on display in the Philips Wing through 17 September 2017. Contact us to to include a visit to ‘Small Wonders’ in your private or family tour of the Rijksmuseum.