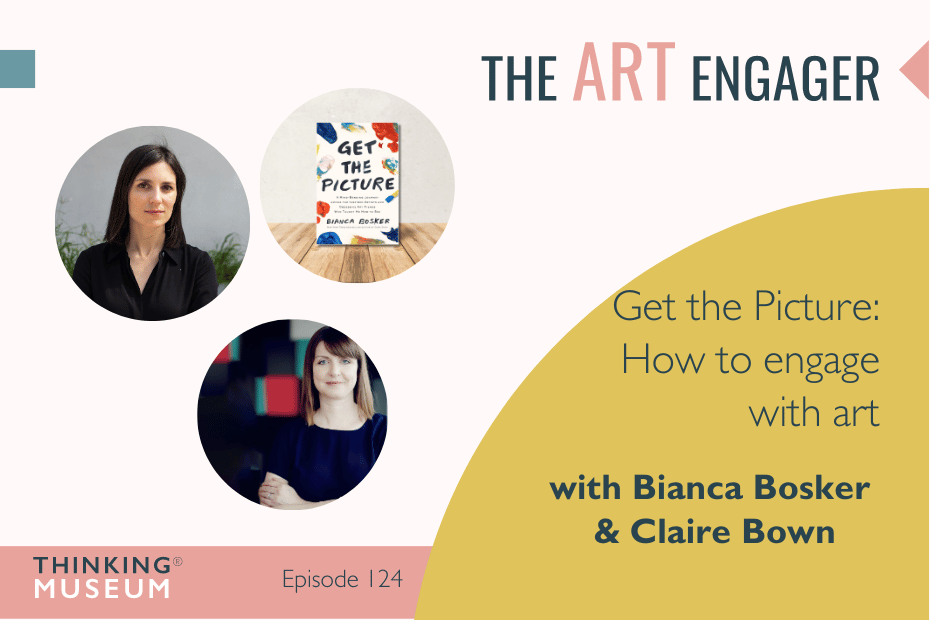

A conversation with Bianca Bosker, an award-winning journalist and author of ‘Get The Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See‘ about why art matters and how we can engage with it more deeply.

Bianca immersed herself for 5 years into the New York art scene as a gallery assistant, artist assistant, curator, museum security guard and more as part of a journey into the secretive world of art and artists

In this chat with Claire Bown, host of The Art Engager podcast, Bianca shares what she discovered about the art world, how her relationship with art has evolved, and how her experiences with various artworks have changed the way she sees the world.

Highlights

00:00 Welcome to The Art Engager Podcast

00:44 Introducing Bianca Bosker

02:44 Bianca’s obsession with obsessions

13:45 International Art Speak, exclusivity and snobbery

19:35 Bianca’s different roles in the art world

24:20 How art helps us to see the world differently

24:37 The Brancusi Sculpture

25:11 Slow looking

27:26 Art is everywhere: seeing the world anew

31:29 Overemphasising context: what role do wall texts play?

37:59 Reimagining beauty

42:11 What does the future hold?

43:34 Wrapping up & links

Transcript

Claire Bown: Hello and welcome to The Art Engager podcast with me, Claire Bown. I’m here to share techniques and tools to help you engage with your audience and bring art, objects and ideas to life. So let’s dive into this week’s show.

Hello and welcome back to The Art Engager podcast. I’m your host Claire Bown of Thinking Museum and this is episode 124. Today I’m talking to award winning journalist and New York Times best selling author Bianca Bosker about her new book, Get The Picture.

But before our chat, don’t forget last week I was talking to Sofie Vermeiren about The Art Bridge, a six year long collaboration between Museum Leuven and a local school exploring how visual literacy can boost children’s self confidence.

If you haven’t checked it out yet, do head back and download Episode 123.

And don’t forget that The Art Engager has over 100 episodes to choose from. Please take your pick from the back catalogue of different episodes to brush up on your skills, be inspired, and learn new techniques. And if you’d like to shape future episodes, get in touch if you have a question for the show, an idea for a theme or a subject we haven’t yet talked about, or if you want to suggest a guest, don’t hesitate to reach out.

I’m always eager to hear from you, especially if you’re an educator doing innovative work with engagement with art, objects and audiences in museums and heritage. Now, you might have heard on social media that this show recently passed 50, 000 downloads, which is huge. Thank you to everyone who has supported this show, whether you’re a new listener or you’ve been here from the start.

Thank you.

You also might know that creating and producing a podcast takes a considerable amount of work. So if you’d like to support the show and help it thrive in the future, you can buy me a cup of tea on buymeacoffee. com/clairebown. All right, let’s get on with today’s show.

My guest today, Bianca Bosker, is an award winning journalist and the author of Get The Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among The Inspired Artists And Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See.

Get The Picture came out this year. Bianca is also the New York Times bestselling author of Cork Dork, a book breaking open the world of wine, and the people who claim to know something about it.

Bianca Bosker is definitely a journalist who is obsessed with obsessions.

In her latest book Get The Picture, we are taken on a journey deep into the art world. Bianca immerses herself as a gallery assistant, artist assistant, museum security guard, and more, as part of a journey to understand why art matters and how we can engage with it more deeply. So in our chat today, we talk about how Bianca goes from mere curiosity about a subject to a full blown obsession, whether it’s in wine or with art.

Bianca shares why she chose the world of art and artists for her latest book. And she talks about how as an adult, she felt she didn’t get art or why it mattered, despite having loved art as a child. We explore the exclusivity of the art world. We discuss International Art Speak and why the art world is so desperate to keep people out.

We talk about some of the roles she immersed herself in for the book and what she learned from them, We also discuss museum labels, wall texts, and whether they are central to understanding a work of art. And Bianca talks about spending long periods of time with artworks, particularly with a Brancusi sculpture, which brought lots of new insights and fascination.

And we talk about beauty and how looking at art is training for taking in the full beauty and chaos of the world around us. You’re going to love our conversation. Here it is.

Hi Bianca, and welcome to The Art Engager podcast.

Bianca Bosker: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me.

Claire Bown: So congratulations on the new book, Get The Picture. I absolutely loved reading it. Very funny, very clever. And I think on many levels, very eye opening too. Actually a listener got in touch with me about a month or so ago and she said, I should read your book.

She said, Oh, it’s coming out soon and you should read it. I think it would go really well with the themes of the podcast. So I have Ellie Ivanova to thank for our chat today.

Bianca Bosker: Me too. Thank you, Ellie. I really appreciate it. That’s so wonderful. And thanks for the kind words.

Claire Bown: So, I’m going to start right at the beginning

I love the way you describe yourself as a journalist obsessed with obsession. And that got me thinking about when curiosity develops from just a mere kind of passing fascination to an obsession. So could you talk a little bit about, yeah, your obsessions?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, absolutely. So I think, when you look at my body of work, I’ve covered a huge variety of different things, everything from witches to supermarkets.

My last book was called Cork Dork, which was about the obsessive world of sommeliers and wine lovers and also this journey to understand these, what I would consider forgotten senses of taste and smell. And Get The Picture, which is my new book, grew also out of my obsession with obsession and is about the incredibly passionate, obsessive world of art and the people who live for it.

And I think that my projects begin when I feel what I can only describe as this seismic activity in my soul, where I, come across something and it destabilizes the foundation on which I’ve lived my life. And curiosity, I think often begins with just, questions and curiosity could be a driving force to go deeper into something.

But that obsession for me is really that feeling in this case, I think that emerged from like, ‘Oh my God, what if everything I’ve thought about how to live my life was wrong?’ And in arts case, this book grew out of this, gnawing fear that just grew more and more intense that, by turning my back on art, I was missing out on something big.

And so, I became obsessed with this question of whether, art was more necessary than I had assumed. And that’s what led me ultimately down this, five plus year journey to understand why does art matter and how do any of us engage with it more deeply.

Claire Bown: So five years, that’s quite a considerable chunk of your life that you have devoted to this obsession, the art world.

Are there any parallels perhaps between the world of wine that you explored in your last book, Cork Dork, and the world of art in terms of passion, obsession, culture?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, I think that there are certainly many parallels. You have obsessive collectors. You have people who rearrange their lives for something that kind of civilians don’t necessarily understand.

And I would include myself in that number, at least at the outset of this journey that became Get The Picture.

I think that one parallel for these worlds, for me, was my own surprise at coming across these groups of individuals who sacrificed so much for something that I myself didn’t understand or appreciate.

In the case of winethere are people who agonize over whether they’re going to drink, wine from Burgundy or Bordeaux. I was at a point in my life where I would agonize over whether I would drink wine from a bottle or a box. That was as sophisticated as I got.

And in the case of art, for a long time, we had not been on speaking terms. Art was a passion of mine growing up, but as I grew older we fell out of touch. I felt alienated. I did not understand what was going on. And so this sort of little forays back into the art world and the people there, their passion, their dedication took me back and made me doubt everything I’d thought about life.

I will also say that this was a bit inadvertent, but I think that both journeys for me personally have a sensory component to them. Cork Dork is really, yes, it was about wine, but on a deeper level, it was for me about learning to savor these, again, dismissed and forgotten senses of taste and smell. I think, Get The Picture, yes, it is about art, but it is also a journey about developing one’s eye.

And so I think that, interestingly, again, this wasn’t intentional at the outset, but there are those parallels in terms of the backbones to the journey I took.

Claire Bown: For sure. And you mentioned there that you felt a sense of alienation. So you were exposed to art growing up, you used to make art, you had art around you.

So, What do you think happened? What stopped you getting it when you got older and made you feel that you weren’t able to figure it out on your own?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, art was a passion of mine growing up. I painted there was a time when I flirted with applying to art school. And then I went off to college and adult Bianca grabbed the wheel and I became very focused on, getting a job that came with a dental plan, basically.

And I think, I had this vague dream and vague plan, that if I wasn’t going to keep making art, at least I would keep experiencing it. And I will say that fantasy crumbled when I actually began seeing, quote unquote, ‘real art’ on a regular basis, and I just felt totally out of my league. I did not understand the vocabulary, I didn’t know the history and I just found The world incredibly intimidating and off putting.

I would go to galleries and museums and I consistently felt like I, was two tattoos and a master’s degree away from figuring out what was going on. And so bit by bit I guess I took the coward’s way out. I withdrew. I just thought, I didn’t know what was going on and I didn’t belong.

And so, bit by bit art and I were no longer on speaking terms. but that change? when I rediscovered my grandmother’s dancing carrots.

I was helping my mom clean out the basement, and I happened to come across a painting by my late grandmother, inspired by her time as a holocaust survivor in a displaced person’s camp in Austria after the war, and basically she’d made these dancing carrots. I’d forgotten all about them, but they were inspired by her time teaching art to children in these DP camps, and she didn’t have any children of her own. She had studied economics, she did not have any art inclination that I know of, and yet in this moment where life turned itself inside out, she turned to art, and from that point forward it.

played a significant role in her life after she retired she ended up making art herself, she’d go to museums she lived in, eventually moved to the suburbs of Chicago, and these Dancing Carrots wouldn’t let me be. I became obsessed with them. They picked off in my mind this question of whether art was more essential than I had assumed.

And again, what I was missing by missing it from my life. And so I decided that I would try again with art. I thought I was a little older, a little wiser, maybe it would go better this time around. And I have to admit that in my initial forays to go and see art, the art still befuddled me. A lot of it, if I’m being honest, was to me, not exactly recognizable as art, random melted candles or strips of plastic on the floor.

And yet the people fascinated me. Again, that obsession just hooked me. And I’d never met a group of people who were willing to sacrifice. So much for something of so little obvious, practical value. If you’ve spent time in the art world, you know the type, right? Artists who treat hundred year old paintings like they’re as essential as vital organs.

And I was interested and surprised to learn that scientists agree with artists. They also consider art a fundamental part of our humanity. As one biologist puts it, it’s as necessary to us as food or sex. And so I just became consumed with this question of, why art? What does it do for us?

And also The people around it had this approach to life that felt expansive and made my own ,existence feel claustrophobic by comparison. And to be fair, they pitied me. A lot of the art lovers that I met told me that I lacked visual literacy, which they said was downright dangerous in a world so saturated with images.

And I just couldn’t stop thinking about what I was missing. And so, that really kicked me off on this journey to see, whether I could see art and whether I could see the world the way these art lovers did. And if so, what would change? And so I decided I wanted to throw myself into the nerve center of the art world and see what I could find out.

And as I quickly learned, no one except me thought that was a particularly good idea.

Claire Bown: So you talk about some of the things there that, I’m smiling, but a lot of the things you’re mentioning there are quite exclusionary tactics in the art world. You talk about this strategic snobbery that’s there for a reason to keep people out.

And you mention in the book that, there are comments about the clothes you’re wearing or the jewelry you’re wearing, or the way the galleries, want to keep out certain types of people, or even in museums, the way we change our behavior or guards are policing our behavior.

So can you talk about that and why the art world is so desperate to keep people out?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, absolutely. I was really taken aback. Look, perhaps I was naive, but, getting access was incredibly difficult. Now, admittedly, I had a rather pushy plan. I wanted to not just interview people, but actually learn by doing.

I wanted to go work at the art world. I wanted specifically to start at a gallery because, for me I just think that, as I now know from experience there is something very different about asking a gallerist how they sell art versus, spending eight hours a day schmoozing with millionaires and selling, a 9, 000 dollar photograph in the back of an Uber during Art Basel on Miami Beach while people are doing cocaine around you.

And at the same time, I really wanted to see how does an artwork go from the germ of an idea in someone’s studio to this sort of quote unquote ‘masterpiece’ that we obsess over in museums because all the decisions that affect an artwork are, I think, decisions that also affect us, right? Our idea of what art is, how we engage with it, why it matters.

And so, yes, I had this admittedly pushy plan, but even then it was so difficult getting access. people told me that my whole plan of wanting to work at a gallery as a journalist was impossible, maybe even dangerous. And, I really felt like an FBI agent trying to get in with the mob.

And I thought, the art world is, the world where people will can their own shit for a sculpture. They applaud free thinking and outside the box approaches.

And I figured, these people that give so much for art, they want to, embrace as many people as possible in the warm hug of art. And it wasn’t until later that I discovered how wrong I was.

So, yes, to your point about the exclusivity. I eventually got a gig. My first job was working as an assistant at this very cool up and coming gallery in Brooklyn, where I started becoming initiated into the strategic snobbery that the art world uses to keep people out.

My boss told me that I needed a makeover, severe haircut, no jewelry. He pulled me aside one afternoon to tell me that ‘I hate to break it to you’, he said, ‘but you’re not the coolest cat in the art world, so having you around, you’re It’s just like lowering my coolness’. And so, basically, I was beginning to be shaped, right?

I think that there’s this idea that if you want to engage with art in these influential circles, you have to play the part. There is a sort of ‘right way’ of presenting yourself, of discussing the art. I was encouraged to tone down my quote unquote ‘superficial enthusiasm’ as you perhaps have noticed and certainly I noticed, I think a lot of art connoisseurs, are lovely people and then when they start discussing art, they exclusively discuss it in this affectless monotone that makes them sound like they’re running out of batteries.

Language, of course, as well. I, I was told to nix certain words from my vocabulary. A piece is not ‘sold’, it’s ‘placed’. I became fluent in art speak. If you’re not familiar with art speak it is basically that overly complex way of speaking where every word is bigger than it should be. So what an art critic calls the ‘indexical marks of the artist’s body’ would be finger painting to you and me. And basically to sound like you know something about art these days, the trick is to sound like a French professor who’s been the victim of a bad translation job, which is perhaps exactly where it emerged.

But art speak is not designed for clear communication. It is this exclusionary code that distinguishes you as someone who does or does not get it. The more I fell into the rhythms of the art world, the more I began to pick up on all the ways that galleries and even public institutions in some cases are designed to keep out the, Joe Schmoes, which was my boss’s term for general public.

So, galleries located less like stores than speakeasies. Many of them are not at ground level because at ground level you have to deal with, and I quote a dealer, ‘random ass people walking in’. and a lot of them have these teeny tiny plaques on the outside that oftentimes omit helpful words like art or gallery.

And then even if you find your way in, you often have to take a ‘schmo detector test’, and I think there is this view that straightforwardness is uncouth, right? A lot of galleries don’t even share their prices. Being borderline hostile is cool. As one dealer put it to me ‘some collectors, they want to be treated rudely’.

But yeah, I think that there’s this phenomenon in which, while you are judging the art, the gallerist is often judging you. And I think that this secrecy doesn’t just apply to journalists. I think it applies to many of us. And I think it is very strategic.

I think that these deliberately erected barriers to entry are a way to build mystique. They’re a way to concentrate power in the hands of gatekeepers. They’re a way to maintain this sense of the art world as being the exclusive purview as a self anointed few. And I do not think that art needs this made up language and all these velvet ropes to be meaningful, to be special.

But I will say that what frustrated me on a very personal level was, I was trying to, develop my eye. gave myself entirely over to the art world, and as I was trying to develop my eye, what was frustrating to me is the way that this strategic snobbery applied, not just to finding the art or buying it, but to appreciating it.

And we can talk more about how that manifested itself, but it was frustrating to find the sort of barriers being thrown up in the way of engaging with art on our own terms.

Claire Bown: Absolutely. I’d really like to ask you about the different roles that you took on during this five year period, becauseyou were a gallery assistant twice, you curated a show you were at the Guggenheim as a gallery guide,

And you also an assistant to the artist, Julie Curtiss. So out of those roles was there one that gave you the keys to understanding and enjoying art again?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, so Each were incredibly challenging and difficult in their own way, which is part of what made them so fantastic, I think, because I was learning so much. Being a security guard, I will say that at the beginning I was So bored that I would just pray that someone would touch a painting so I could tell them not to.

But I will say that I think working as a studio assistant for up and coming artists really was transformative in my relationship with art, but also my relationship with the world. And, the deliberately erected barriers to entry that the art world puts up applied also to savoring the art and I was getting frustrated as I worked at one of these galleries with just how much art connoisseurs seemed to focus on everything outside the work itself.

All the things that I thought were irrelevant to appreciating an artwork, where an artist went to school, who they’re sleeping with, who their friends are, who else owns the work, were, I was quickly made to understand, actually vital to understanding it. And all of those things that I’m describing, school, the friends, that is referred to as context, right?

That’s the context around the piece the web of names around an artist. It’s the social capital that goes along with them. And people spent surprisingly little time discussing the merits of the artworks themselves. And instead, discussing the context of the pieces and of the artists.

And that frustrated me. It felt like I was being encouraged to outsource my eye to the hive mind, and I think all the emphasis on context also felt like one more way to keep out the ‘schmoletariat’, because these connoisseurs become a lot more important if we’re told that we need, an advanced, degree and years of going to art fairs and familiarity with artists bios and, the right haircut to commune with an artwork.

I think it was really like sitting on artists studio floors, stretching canvases and painting backgrounds that something clicked. And I think I began to understand how to savor art like an artist, how to really look at an artwork face to face. And that meant slowing down, paying attention to the physical form, and examining the artist’s decisions.

This was a departure, I think, for me and what I had heard. I think for the last hundred years or so, we’ve been told that what really matters about an artwork is the idea behind it. We can think in part, Marcel Duchamp and, putting a urinal on a pedestal for this. He was all about, the idea of an artwork as opposed to, just the retinal titillation.

where there’s this idea that the thought trumps the thing.

And yet, making art, if you’ve been to an artist’s studio, it is a blistery business. It is practically athletic. I nearly maimed myself with a stapler gun. I watched, the artist Julie Curtis sweating for hours to get the right shade of gray.

And as she herself put it, ‘an idea is not a painting. Painting is constant decision making’. And so, I do think that Seeing artists at work helped me find a way to stay in the work. And so I eventually went back and I was looking at exhibits. For the first time in my life, I stopped reading the wall labels.

And it used to be that whenever I went to a museum or a gallery and they didn’t have that paragraph long explanation of a work, I thought it was just rude. I was like, you have to tell me what the answer is! I need the answer! And having worked in artist studios having spent time with artists, I took first of all, a piece of advice that one gave me, which was to just notice five things in a work.

And they didn’t have to be grandiose; this is a meditation on, on, feminism in the age of hyper capitalism, like it could just be, this texture gives me the shivers or I don’t know, like I want to lick that palm tree. And I think that, it was staying in the piece that really let me brush away the snobbery, step away from the context, and like I said, experience the art on my own terms, see it face to face with less pretense and more mystery than ever before. And I would say that was a transformation. It was a way of seeing that paid dividends for me far beyond the white cube. The way that artists see the everyday world is so exciting and carries so many lessons for all of us.

Claire Bown: I love that. You were just reminding me of therelationship you developed with the Brancusi piece in the Guggenheim when you were working there. In the second half of the book, I really noticed

there’s a relaxing, a slowing down and you can really see it when you’re talking about spending those hours in the Guggenheim, bored stiff as you say, just

Thinking about what might happen if I spend 40 minutes at this post looking at this artwork. So tell me a little bit about the Brancusi and what I’ll do is I’ll include a link to the piece in the show notes. And I’ll let you talk about it first.

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, I will say that, first of all if context is your jam there’s no wrong way to engage with art.

I think that, as I said, the guiding questions for me were like, why does art matter and how do any of us engage with it more deeply? And I hope readers will agree that there are many different answers to those questions in the book because, These are not simple answers there’s not like a multiple choice answer to it.

Now, that being said, I think that I certainly found paths that resonated more with me. And I was able to exercise some of these looking techniques I learned in artists studios while working as a security guard at the Guggenheim. There are a few reasons I decided to work as a security guard, but one of them was That I was curious to know, how would being around art for hours on end with no possibility for escape, influence my relationship with art?

And I will say that, yes, as I said, I was a little bit bored at moments in the beginning and I began to break up that boredom by giving myself different exercises on each topic. And one of them was to spend 40 minutes looking at a single artwork and 40 minutes because that was the duration of our post.

We’d spend 40 minutes in one place, then we’d rotate to the next one and so on and so forth throughout the day. And on one afternoon, I found myself with a Brancusi sculpture and I’m not gonna tell you the name of it because I think it just immediately cuts off people’s descriptions and stops them from seeing all the permutations, but it’s it’s made out of white marble, and it looks like someone squeezing toothpaste onto a toothbrush, except the toothbrush in this case is a pedestal and it’s just like the sweep of this the smoothest, gentlest marble.

I just wanted Squeeze it like it was just so irresistible to pet it. It felt like velvet on my eyeballs just to watch it over and over. And yeah, this was a piece, I will say that the only time I’d ever spent 40 minutes staring at a single artwork before this was never. It took like the threat of getting fired and a million security cameras to stop me from pulling out my phone, right? And distracting myself with something else. But the exercise was incredible. I noticed new things in that piece after 40 minutes, after four hours, after four weeks.

And I began to develop this relationship with the piece and with a lot of the pieces at the Guggenheim. I began to feel what I can only describe as love for this sculpture. It was this feeling that I recognized from being in love. It was this feeling that I could be around it for as far as I could see into the future without getting sick of its company.

And, I think that slow looking exercise, that sort of forced bonding with an artwork, opened me up not only to seeing more in the work, but in seeing more in the world. One of the things that I found so enthralling about how artists engage with the everyday is the way that they’re able to turn this art mindset onto quotidian life. Julie Curtiss would find inspiration from, I don’t know, blob buildings in Midtown or a parked motorcycle on the side of the street. And she would look at objects in the everyday world as though they were artworks, right? With this willingness to linger for an extra beat on why, just to really examine their form, to ponder the beautiful mystery and impossibility of some of the things that we surround ourselves with. And I think I began to experience it, I would leave the Guggenheim after my shift and I would see art everywhere, right?

And I think that helped me reach an answer to why art is so fundamental to our existence. And interestingly, scientists and artists have reached a similar conclusion on this front.

And that is that art helps us fight the reducing tendencies of our minds. We do not go around seeing the world like video cameras. We do not see things objectively and dispassionately. it’s not like everything is in focus when we look at the world around us. our brains are more these trash compactors.

And so when we look out at the world, we have these ‘filters of expectation’ that descend and are constantly, preemptively dismissing, organizing, sorting, compressing, We’re, shaping the raw data coming in even before our brains get the full picture. And I saw this in action in Artist Studios, whose art helps us lift those filters of expectation.

Art introduces a glitch into our brains. It’s a glitch that is a gift. It is a glitch that knocks our brains off their well worn pathways and really help our minds jump the curve, which is just so exciting to experience. And I think that you can, notice that in that moment where you step out from a gallery and see things by unseeing them.

Another artist, Liz Ainsley, talked about How something as simple as riding a subway, when you lift those filters of expectation, when you allow your brain to take in the full nuance, chaos and beauty of the world around you, it becomes this impossible miracle.

We’re in this underground tunnels. There’s these little constellation of colored seats. The whole thing becomes amazing and inspiring. And As I said, I think that jostle that art provides our brains, we can begin to experience it everywhere if we allow ourselves to engage in that exercise of lifting our filtered expectation and fighting the reducing tendencies of our minds.

Claire Bown: Yeah, all too often we think we open our eyes and it’s like a camera opening its shutter and it’s completely not. We see with experience, we see with our feelings, our ideas, our opinions, but also, We get used to seeing things, the art on our walls at home, the things that we go and see in museums as museum educators, we get used to the art that we’re talking about with groups.

And sometimes, as you say, it’s really important for us to try and ‘unsee’ and get less habituated to the things around us and have those kind of sparks of surprise I love the scene you’re talking about being in a supermarket in the frozen food aisle.

And just suddenly you see everything for all its kind of glory and brashness and all the words and the colors jump out at you. And yeah, I think that you’re absolutely right. Art can help us to see better, to see the everyday world better as well.

Bianca Bosker: Well, I think I had this experience of realizing that being around Julie, the artist I worked for, was like being on drugs in which like everything takes on this extra dimension. It’s like the world is a little bit more colorful. You have these moments where you feel like, a tree is performing just for you. It’s, it was amazing to read it was all just Huxley’s meditations on being on, I don’t know, some hallucinogenic compound where he would talk about noticing like the, just the folds of fabric.

And I was like, I don’t think you have to do drugs. I think you just have to do art.

Claire Bown: Absolutely. You’re reminding me of what you said aboutknowing the titles of artworks and reading the label you say, it’s like having a conversation with someone’s constantly interrupting you.

so interested in hearing your thoughts about this. Cause I, I wrote a post last year about wall labels. It was on social media, it was just questioning whether we need them in all cases, whether we could have a different experience with art if we were just focusing on the art itself. And this post,

got shared lots of times, but there were lots of really outraged comments on it. People were not happy with the idea of doing away with the label, not knowing the context, not knowing the artist and the background. And as you say, there’s no one right way to look at art, but there are lots of different ways that we can look at art.

And my theory was that why not open ourselves up to the possibility of looking without a label?

Bianca Bosker: Yeah, it’s interesting. I’ve been to a few shows recently that have dispensed with labels.

and it really changes the experience. It leaves you to fend for yourself, which can be uncomfortable at first, but as artists were fond of reminding me, art is supposed to be uncomfortable. I think there can be a beauty in that discomfort as long as you’re willing to wrestle with it.

of course there are times and instances where the wall text can be helpful. I remember going to see an artist retrospective with an artist, and it was so interesting the way that she really examined the years in which the works were made and the medium in which they were made, and that was this other layer of information that allowed her to get another view onto the work, right?

At the same time, I will confess that during my time working as a security guard at the Guggenheim, I became extremely skeptical of wall labels. Like they really they hindered people’s interpretations. there was a piece that was a locked post, meaning I couldn’t stray more than 10 feet away from this particular piece, because we had to protect the layer of dust gathering on the artwork.

It was a Joseph Beuys piece. It was this dangling bare light bulb over a wooden table and chair with the aforementioned all important layer of dust. And I mentioned I had relationships with different pieces this was definitely an enemy sort of relationship, like this work I just thought was so ungenerous, I did not understand what it was about, the wall label was to me totally useless, I, it read like it was describing an entirely different piece.

And I would make people stop and struggle with the piece with me. And I was so impressed, a lot of the visitors, they’d never heard of the artist, they’d never seen this piece before, and their interpretations were incredible. We would travel, to a Soviet interrogation room, to a Hungarian prison, to a Colombian classroom. We just traveled the world without leaving the ramp, of the Guggenheim. AndI think what bothered me about the Wall labels was first of all, that they spoke this voice of God imperiousness that implied that there was ultimately a single right answer to the work. And the reality is that, these labels tend to be written by art historians, by curators, who are coming at it with an art historical perspective, and that is a totally valid and interesting interpretation of the work, but it’s certainly not the only one. And yet I think that a lot of us, myself included, have looked to these wall labels as like the answer key at the bottom of a word search. And we’ll give ourselves a second with the piece, you know, there are studies that show that we spend more time reading a wall labels than looking at the artworks themselves.

I think the other thing that drives me absolutely nuts about wall texts is the art speak. I would love if I could name a museum that I think this is not the case, but That is what is not coming to mind at the moment. In general, wall text to me feels like the world’s hardest reading comprehension exam.

I would spend hours with some of these wall labels at the Guggenheim, and I still have no idea what they were trying to say. And as a writer, I got this sort of like allergic reaction. Because I do think that as a writer if I can’t say something simply, it means that I haven’t fully figured out what I’m trying to say.

And I think that it’s bizarre to me that these institutions put so much effort into these shows. Just moving artworks around the world, the insurance, the expense, the advertising, so much care is put into these exhibitions, and yet we have these public facing texts that feel they haven’t put the viewer’s best interests first.

wall texts are so public facing. If we are going to have them, and I’m not sure we do necessarily need to have them, I would just love to see them be more legible. And I apologize if that’s, my own ignorance shining through, but I do think that we could probably make them written a little bit more for humans.

Claire Bown: I think it’s more often the exception rather than the rule that you will get interesting, interactive wall texts that might encourage a conversation. There are museums doing it, but there are more museums that still have these more old fashioned traditional wall labels that, as you say, tend to give you the one right answer.

And the issue with that is that it’s shutting down other perspectives. As you say, it’s limiting our imagination to look at a piece and run with it and think about, Oh, what is it that this could be?

It really shuts down those possibilities.

Bianca Bosker: Or having a physical experience with the artwork. I do think that the modernist started this idea that looking at art was more philosophical than physical experience. It was a little bloodless.

It was about the ideas. And,

I think that I at least had to relearn how to engage with work at a physical level, to simply be able to enjoy a photograph, not for it’s architectural tectonics or it’s cubist reference, but for the way it just made me feel good.

I don’t think that’s a lesser experience of the work. going back to the artists and the way they engage with their work. Julie would treat her art, her artworks, like they were these other people in the studio. They could be rambunctious, they could be assholes but they had bodies and she belabored every, stroke and hair of that body.

I do think That is a helpful way of thinking about our relationship with art. The same way that sitting down with a person at dinner is very different from seeing them over FaceTime, seeing a work of art in person is very different from seeing it on Instagram. You are a physical being in space.

It is a physical being in space. It has a physical form. it’s big, it’s small. All of those things are telling you something as a viewer. I also think that beauty has been de emphasized in an injurious way.

For the last hundred years or so, the art world has been on the warpath against beauty. Not just the art world. I would say it’s like the intelligentsia. There’s a sort of sense in polite society that beauty is to be avoided.

It is corrupted and corrupting. Falling for its charms is a sign of moral weakness. It’s passé. And yet, I think we ignore beauty at our peril. We may think that we’re done with beauty, but beauty is certainly not done with us. It is an intrinsic part of being human. And beauty doesn’t have to be the visual equivalent of a vanilla cupcake.

I think that, art teaches us how to see beauty in more places than we ever did before.

Beauty is just something that pulls us deeper into life, that nudges us into a place where we’re wondering about the world and our place in it. And in that sense, I think there’s something nihilistic about denying beauty in the same way that embracing beauty and seeking it out is a way to simply engage with life more deeply.

It is an excited ‘hell, yes!’ To what life has to offer. And I think ultimately that rather than Perhaps shunning or demoting the idea of beauty, this is something that museums and institutions and galleries should consider and perhaps lean into.

Claire Bown: So tell me about what you came away from this experience with. Do we need any of this stuff that the art world wraps art up in?

Bianca Bosker: So first of all, I hope that it’s a continuing journey. I think there’s still so much more that I want to see and experience. And it’s of course very hard to summarize what was such a life changing experience.

In a short answer, I will say that I consider this book a love story. Despite all of the criticisms that I may level and the things that I think could be better. I think nonetheless, like a love story, like there’s agony and ecstasy, right? And but ultimately I hope that readers agree that It’s ultimately a celebration of what art has to offer us.

I came to the conclusion that I do believe that there is an artist in each of us to the extent that we struggle to keep our brains from compressing our experience of the world. I think art is a choice. It is a fight against complacency. It’s a decision to live a life that’s richer and more mind blowing and ultimately more beautiful.

I think that, in terms of my own relationship with art, first of all, I think I see art everywhere now. I ended up meeting this performance artist who had spent several years performing as an ass influencer on Instagram

and I met this person because they were an artist had invited me to their opening, and at the opening, this ass influencer Mandy allFIRE had invited her fans to come and have their faces sat on until they couldn’t take it anymore.

And I went to this opening, again, just knowing what I had read about in the press release, and thinking, this was too much we have gone too far. And I ended up actually having my face sat on at the opening, and Well, I couldn’t stop thinking about this artist’s work for various different reasons.

And I will say Mandy allFIRE and Julie Curtiss and some of these other people I met pushed me to this place of having a much more expansive idea of what art is. I think we live in the aftermath of these rather arbitrary decisions made by status conscious Europeans in the 1760s that Essentially elevated certain things to the pedestal of fine art and dismissed everything else as craft. And it used to be different.

It used to be that anything involving human ingenuity or skill was considered art. So passing laws was art, training horses was art, making a sculpture was art. But I think that, understanding the origins of some of our hangups around art was freeing and spending time with artists was also freeing in the sense that, it opened me up to having these experiences of art, that moment where your mind gets jostled and jumps the curb and I don’t know, I think that ultimately, I’m so thankful to all the people who played a role in this journey for introducing me really to the way that looking is an adventure.

Claire Bown: Love it. You mentioned there that it’s an ongoing journey. What’s next for you? Do you have any new obsessions that you’re currently thinking about or wanting to dive into?

Bianca Bosker: Well, we’ll see. It’s funny. my attempt to bond with art, grew out of Feeling like my life was claustrophobic compared to the expansive existence of these art fiends who basically behaved like they’d accessed these trap doors in their brains.

And I think that my life has become more expansive, but at the same time I feel like I’ve discovered new boundaries in the process that I want to push beyond. I will say that I keep a running list of story ideas in my phone and It’s just veered off in totally weird and surprising directions.

Artists have this amazing ability and freedom to just follow their interests and incorporate it into their work. I remember talking with Julie about the experience of being a journalist and the way that, I write something and then I share it with an editor.

An editor makes suggestions and changes and comments. And she was like, that sounds miserable. She was like, that’s terrible. Like someone’s shaping your work. And just you have to work with these confines. And of course artists work with so many different confines, but it is a different process.

It is a different creative process. And so, yeah, I don’t know. But I’m so grateful for the new approach to life that I’ve learned in this process. I think art is practice for appreciating life, but it’s also practice for creating a life worth appreciating.

Claire Bown: I’d just love to finish by telling everyone to buy your book. It’s called Get The Picture, a mind bending journey among the inspired artists and obsessive art fiends who taught me how to see. It’s already out in the US and by the time this podcast comes out, it will be out in the UK and Europe too.

Bianca Bosker: So a huge thank you to Bianca for joining me on the podcast today. Get The Picture is out now in the US and Europe. Read this book, it’s funny and clever and will change the way you think about and engage with art. Go to the show notes to find all the links for Get The Picture and for getting in touch with Bianca too.

Claire Bown: That just about wraps up this episode. Thank you for tuning in. Until next time. Bye.

Thank you for listening to The Art Engager podcast with me, Claire Bown. You can find more art engagement resources by visiting my website, thinkingmuseum. com, and you can also find me on Instagram at thinkingmuseum, where I regularly share tips and tools to on how to bring art to life and engage your audience. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, please share with others and subscribe to the show on your podcast player of choice. Thank you so much for listening and I’ll see you next time

Links for Bianca Bosker and Get the Picture:

Bianca Bosker on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bbosker/?hl=en

On Twitter: https://twitter.com/bbosker?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

On Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/bianca.bosker

Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Get-Picture-Mind-Bending-Inspired-Obsessive/dp/1911630466

Bookshop: https://www.waterstones.com/book/get-the-picture/bianca-bosker/9781911630463

The Art Engager Links:

- Sign up for my Curated newsletter – a fortnightly dose of cultural inspiration

- Join the Slow Looking Club Community

- Support the show here

- Download my free resources:

- How to look at art (slowly)– 30+ different ways to look at art or objects in the museum.

- Slow Art Guide – six simple steps to guide you through the process of slow looking

- Ultimate Thinking Routine List – 120 thinking routines in one place

- Other resources

If you have any suggestions, questions or feedback, get in touch with the show!